Introduction

Scroll down to listen to the next section

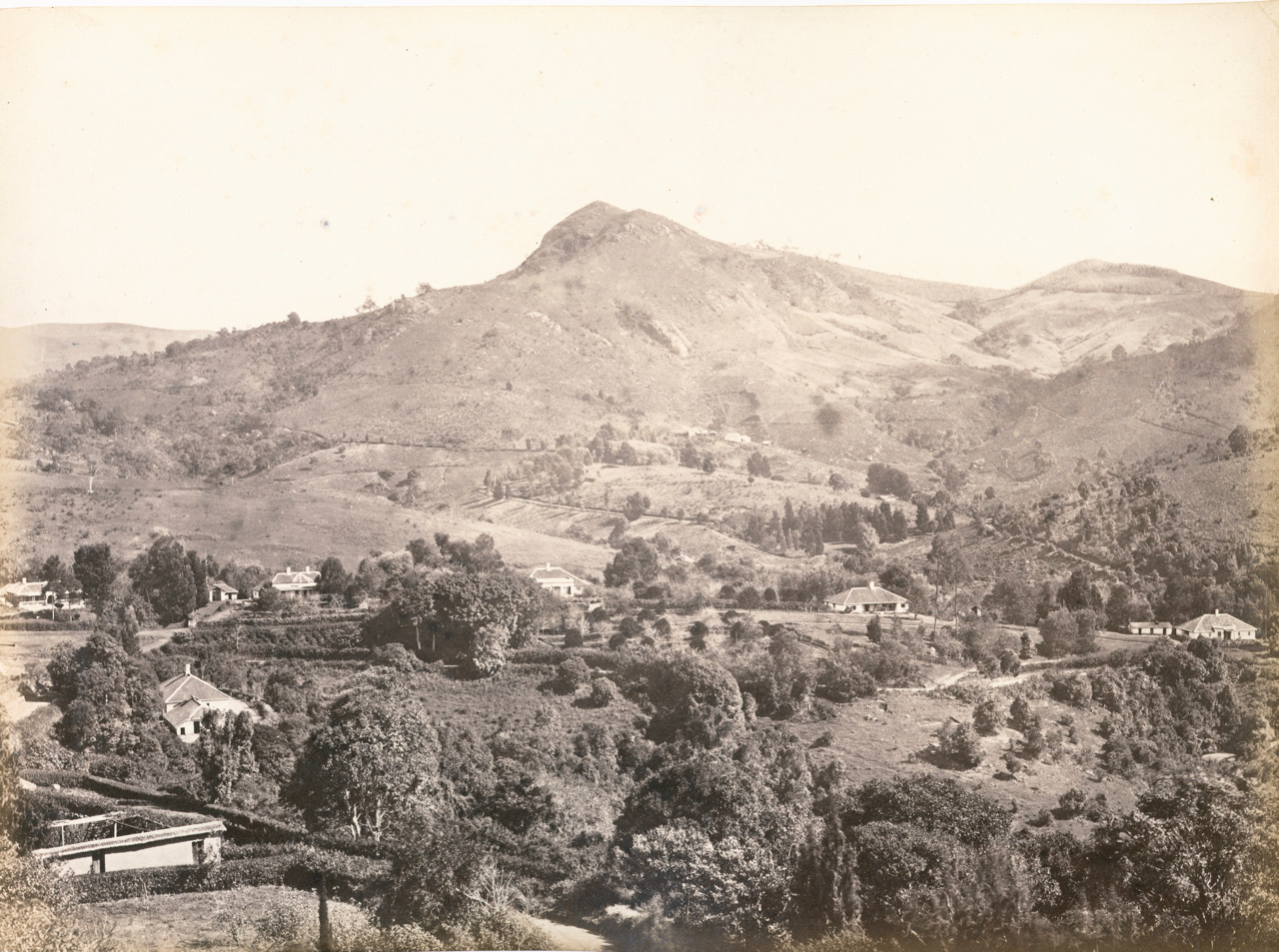

Situated in the Nilgiri District which lies in the Southwest corner of Tamil Nadu in India, the little town of Coonoor can be described as the gateway to the much famed tourist destination, Ooty.

The township lies at the head of a grand ravine and pass which bears its name. Although the ravine faces the Southeast, a considerable portion of the town is chiefly built on the western slopes of one of the valleys at the head of the pass, and over the lower slopes of the spurs of the two hills.

Coonoor with its rugged knolls, profuse vegetation, and a colour scheme which is both bright and warm, has always been described as a scenic, delightful and healthy retreat. Although the town has grown over the years, it still retains its old world charm and still breathes of the soft south, with a climate that is mellow, moist and relaxing, one which is calculated to induce a dolce far niente life even in the most jaded lionizer.

The first mention about Coonoor as a European settlement is seen in the first edition of

Dr. Baikie’s ‘The Neilgherries’ published in 1834, here he mentions an encampment of officers and men of the Pioneer Corps, where the present day railway station now stands.

That Coonoor had in the least a temporary population of six Europeans in 1834 is quite certain, for Baikie mentions Lieutenants Vardon, Dibmas, Rundall, Elliot, and a Dr. Driver of the Madras Sappers and Miners, and yet another Dr. Palmer, all resident at Coonoor, as subscribers for his book. He further speaks about a public bungalow situated near the present day courts as the only means of accommodation, where a traveller could according to regulations spend three days ; but goes on to state that 6-8 very comfortable bungalows belonging to the pioneer officers would soon be available for rental, as the work on the ghat had almost been completed.

Nothing much appears to have changed in 1835, when Dr. P. M. Benza engaged in a geological survey, came up with his map, with Coonoor being marked with the aforesaid traveller’s Bungalow, and the pioneer lines with the officers’ accommodation a little below.

Scroll down to listen to the next section

In 1838 Dr. DeBurgh Birch in his topographical report of this district, dismisses the region of Coonoor as a station, but states that it cannot go unnoticed, as it had once been the place of encampment for the sappers.

The opening of the Coonoor Ghat looks to have changed all this, with travellers preferring this route to Ootacamund, and Coonoor with its milder climate being situated at the head, appears to have attracted a few settlers. The District Gazette speaks about Mr. H. R. Dawson, Major-General Kennett, Major-General Wahab, and Mr. Norris, who according to land records owned houses, the first of these and a Captain Vallancey, owning between them about 250 acres of coffee and mulberry.

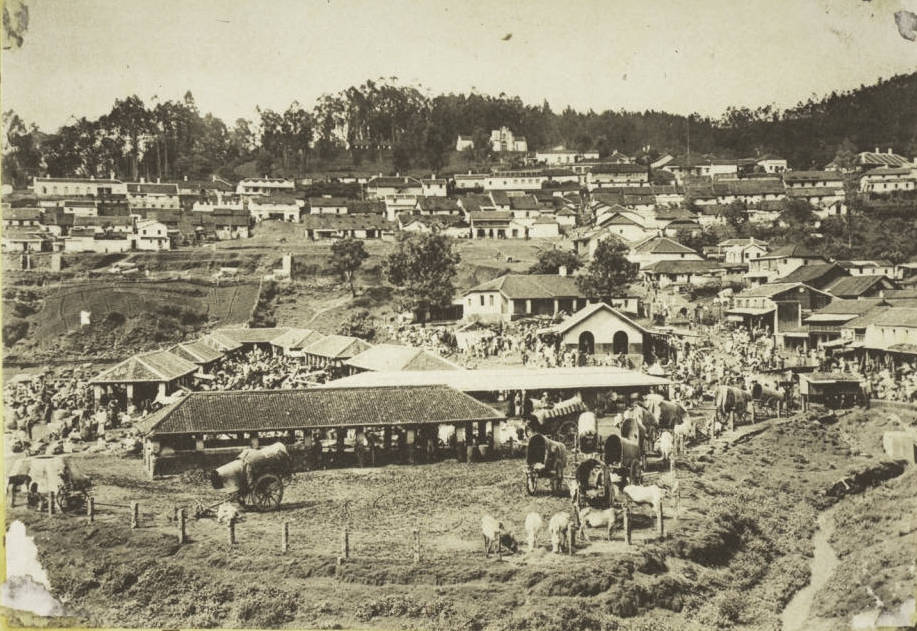

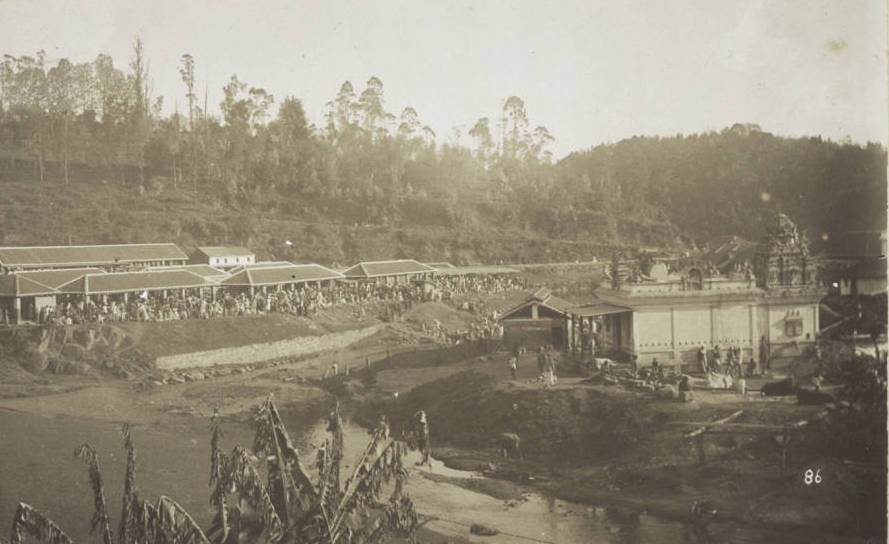

The survey carried out by Captain later Colonel J. Ouchterlony in 1847, describes Coonoor as having a total population of 397 souls, with just seven European inhabitants. He states that the settlement was sited on the crest of a range of hills running down from the Coonoor Peak. The European residences fourteen in all, and a hotel, were placed on the rounded tops, while those of the natives numbering about 131 along with the bazar, appear to have been situated in the hollow below. He as well speaks about a masonry bridge across the Coonoor Stream, of a ‘chettrum’ for Indians, about cheap labour available at 2 annas per diem, about bread being supplied from Coimbatore, and about increased traffic along the ghat ; with bullock carts numbering by thousands ascending it on the market day of Ootacamund. The acreage under coffee appears to have increased but that of mulberry was on the wane.

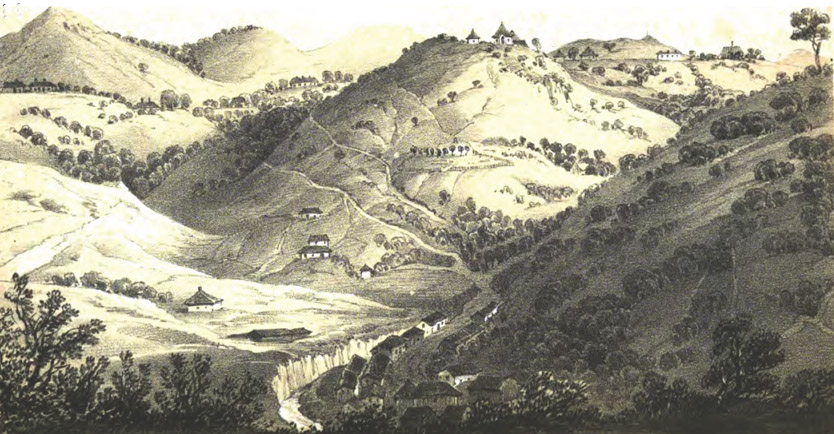

Ouchterlony’s statements are further corroborated by the sketch made by Lt. Burton of the Bombay Army at around the same year evidently from the traveller’s bungalow. It shows about 9 European households and a hotel which he identifies with ‘Davison’s,’ the earliest of such in Coonoor, which later became the ‘Glenview,’ on the site of which presently stand the buildings of the UPASI. Sir Francis singles out one of the houses as ‘The Lodge,’ the property of Major-General Brackley Kennett one of Coonoor’s earliest inhabitants. The ‘Woodcote’ of Mr Lascelles, and the three properties of General J. W. Cleveland, ‘Balaclava, Alma, and Inkerman,’ which were known to have existed around that time are not included, as they lay above and behind the view from the which Burton made his sketch.

Scroll down to listen to the next section

The second edition of ‘The Neilgherries,’ published in 1857, speaks of 24 well built, and well furnished houses, a few of these being rented out with rents varying from 120 to 50 or 30 rupees per month. In addition he speaks about the hotel with its four detached bungalows, the All Saints’ Church, and the market where all the shops were owned by Indians but were rather ill supplied.

When Coonoor was declared as a municipality in 1866, either on 19 Oct according to H. B. Grigg in his District Manual, or on 1 Nov as per Sir W. Francis of the Madras Gazetteer, the population doesn’t seem to have increased much. It numbered just around 1,400 odd individuals, and there appear to have been 39-42 bungalows belonging to the Europeans and about 263 native houses and shops.

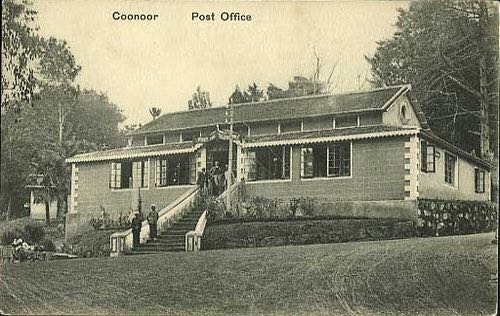

Coonoor by this time had a post office, a third class telegraph office, a hospital, a dentist’s establishment, a day school, yet another hotel called ‘Gray’s’ in addition to Davison’s which was now called Glenview, and a transport company attached with a refreshment room. A library, a music depot, and a European general store were a few of its luxuries

The chief achievement of the Coonoor Municipal Commission after its inception can be said to be the putting in place of a proper water supply and drainage system, and the extension of the market which in 1908, stood third in the presidency in terms of revenue generated. By 1871 the population had more than doubled to 3,058 individuals dwelling in 536 houses, and by 1881 it stood at 4,778 individuals.

Coonoor now had a permanent resident European population mostly made up of planters, and now boasted a regular police station, a sub-jail, a deputy tahsildar’s office, and that of a sub magistrate. The number of hotels had as well gone up to three for in addition Glenview and Gray’s, one more, the Hill Grove, had come into existence. Also gone for good were the days when bread had to be transported all the way from Coimbatore, for the town now had a couple of bakeries of its own.

As on 1901 the residents or the cold weather population as it was called stood at 8,525, and by perusal of the map available for that period the town had expanded westward. It was considered to be so crowded that a further westward extension was under consideration. A full tahsildar was appointed in 1905, and the station was made the headquarters of a European Head Assistant Collector.

It is a far cry from those days and the present, and Coonoor is much more congested than ever, her population now having crossed the 50,000 mark, and ironically it still largely subsists on the legacy of the public works carried out by the British of the Raj, whatsoever their motives might have been.

Her Ghat

Scroll down to listen to the next section

‘The rolling English drunkard made the rolling English road,’ goes the poem of G K Chesterton, and it is again the Englishman, drunk or sober, who can be credited with laying down the first roads of the district, and the most important of them all, the Coonoor Ghat connecting the hill station of Ooty with the railhead at Mettupalayam.

Before the fall of Seringapattinam and the advent of the British, access to these hills were through the Passes, accessible only to persons on foot or to draught animals, the most prominent among these the Sundapatty Pass connecting Mannarkad and the group of villages known as Melu-natha. The need for a proper road arose when Ootacamund and its surroundings started gaining popularity as a sanatoria and a summer retreat, and was completed in 1833. It was constructed by Lt. LeHardy and his corps of pioneers, but the original alignment was so faulty and the gradient so steep, that it was relaid by Colonel and the then Lieutenant Law, after whom the scenic albeit highly polluted Law’s Falls is named, in 1871. The remnants of Lt. LeHardy’s Road still remain as the Old Mettupalayam Road.

The new road is indeed a reeling road, a rolling road, that rambles round the steep Coonoor Ghat, starting at Mettupalayam and crossing the Bhavani River, before traversing the picturesque village of Kallar with its Areca Nut plantations, from where the ascent begins.

The view in the ascent is indeed breathtaking, the road winding through deep ravines and under lofty crags, while far below rushes the Kallar, and on the opposite stands the grand bluff of the Hulical Droog, before reaching the head of the Ghat, from where it levels out to reach Ootacamund some 18 kms away.

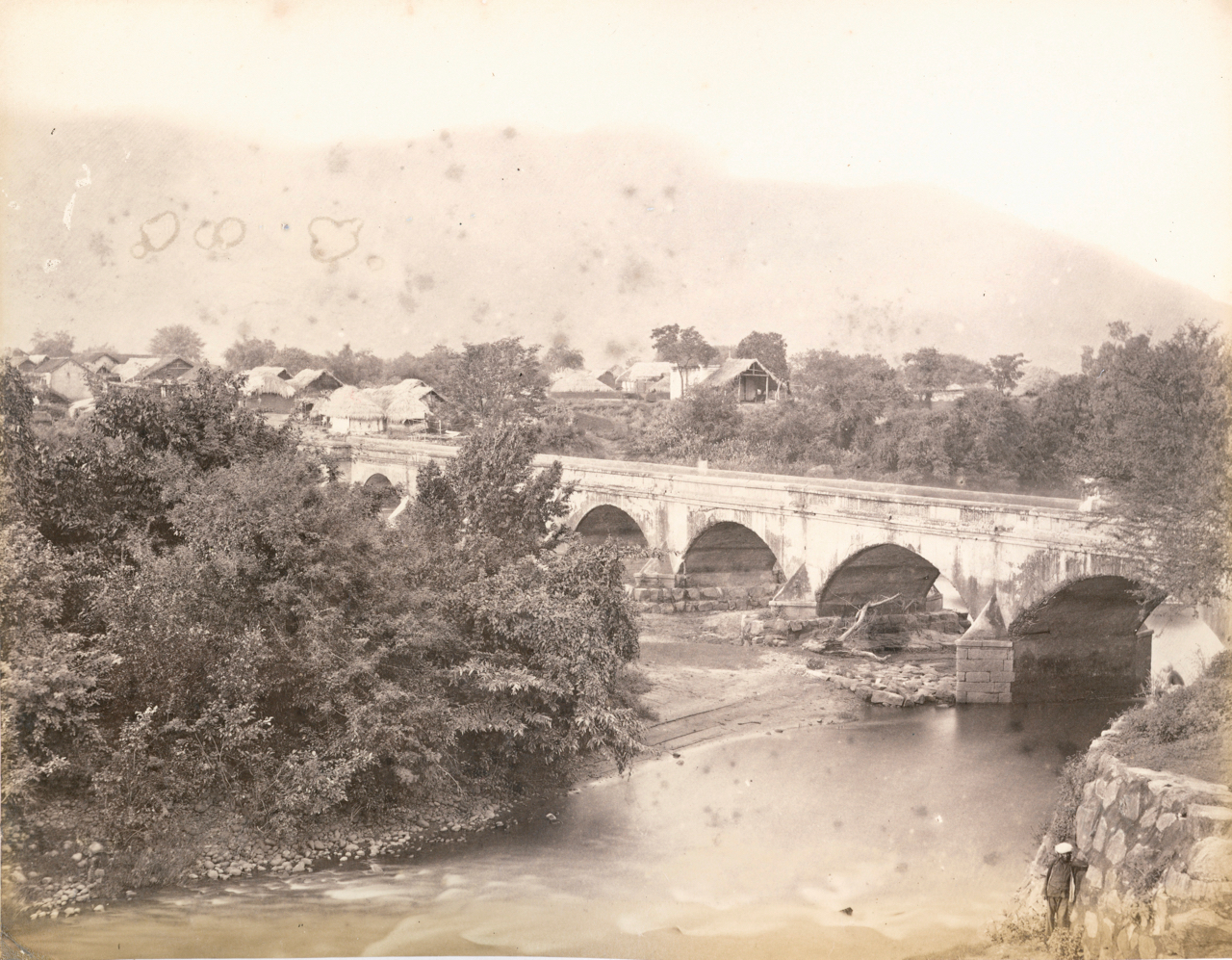

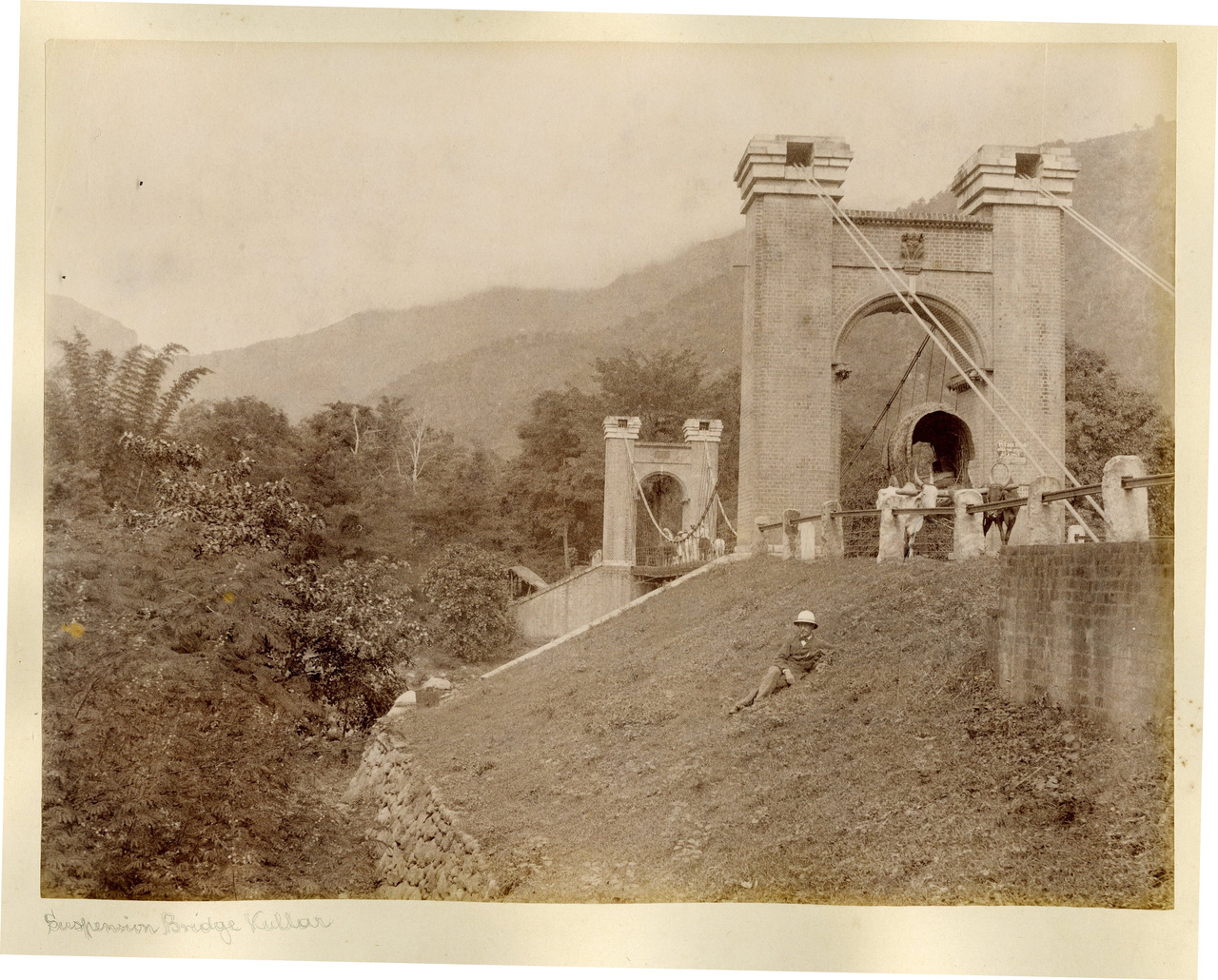

The Rivers Bhavani and Kallar were initially unbridged and had to be crossed by coracles, and most of the mountain streams were bridged over with wooden bridges. Later the Bhavani was spanned over with a masonry bridge and the Kallar initially had a suspension one, the remnants of which were demolished recently. The masonry bridge, the suspension bridge and the other wooden bridges, gave way to regular steel truss bridges in the 1890s.

The only remnant which stands as a mute testimony of the massive work that was undertaken to make what was once a mere track meant for cartloads, tongas, and people on horseback, to one which is now motorable, is the ramshackle shed belonging to the Public Works Department, which once used to be the office and residence of the Section Officer in-charge, just above Burliyar.

Her River

Scroll down to listen to the next section

The three streams that form the Coonoor River originate as sparkling rivulets of beautiful spring water, from amongst sequestrated wooded vales and in sylvan nooks, where masses of noble trees rise in all their glory, and the jungle floor is carpeted with crisp fallen leaves and adorned with a lush undergrowth of mosses, ferns, and rare endemic balsams ; forests primeval and the home of many specialised lifeforms.

The upper and central streams unite near the Old Coonoor Bridge, and from here, they continue further to the lowest part of the town proper, to join the lower stream, before falling over the rocky lip of the plateau. The combined waters then rush down the gorge, as the Coonoor River, which ultimately empties its volume into the Kateri Stream near the quaint little railway station of Runnymede.

The entire course of the river abounds in picturesque cascades, beautiful yet not famous, but, representative of many such falls in this district.

Of all the delightful bits found on this stream, the prettiest is the Law’s Fall, so named after Lieutenant later Colonel G. V. Law, the officer who traced and laid the present Coonoor Ghat.

Her First Post Office

Scroll down to listen to the next section

That the first post office of this district came into existence at Ooty somewhere around 1826 is well recorded. The next three to come up were those of Coonoor, Kotagiri and Wellington in chronological order. The one at Wellington is recored to have become functional in the year 1855, but as to when those of Coonoor and Kotagiri came into being are unavailable.

That some sort of post office must have existed at Coonoor between 1842 and 1847 is a certitude. The former was the year when Coonoor traces its roots as a settlement, and the latter was when Captain later Colonel Ouchterlony completed his survey of the district.

On the subject of revenue obtained from the hills through the then nascent postal system, Colonel Ouchterlony makes a distinction ; revenue derived from the District Post Office which is no doubt Ooty, and that from others which could have only been Coonoor and Kotagiri, Wellington not being operational at that time.

As to the exact location of this early post office of Coonoor, there is no clue. By 1880 and according to Grigg of the District Manual, it appears to have been shifted to the traveller’s bungalow situated on the premises of the present-day courts.

Have used the word shifted, for till 1857 the traveller’s bungalow which Grigg mentions was still serving the purpose for which it was built for, and not as a post office.

The post office in the late 1890s appears to have again been shifted. Its new location is seen in the municipal map appended in the District Gazetteer of 1908, marked around the whereabouts of the present-day ‘Abdulla Sports.’

Her First Church

Scroll down to listen to the next section

3 September 1851 was the date on which the cornerstone of the first church in Coonoor, dedicated to ‘All Saints’ was laid.

Built on a ridge, this 167 year old place of worship with its lofty square tower, stands amidst a beautiful graveyard planted over with weeping cypresses. It commands one of the finest views in Coonoor. To its east is the ravine which separates it from the Tiger’s Hill, and through which flows the lower stream that feeds the Coonoor River.

Described as one of the prettiest churches in India, it is built in the Gothic Revival style, replete with pinnacled buttresses, tiled roofing, and glazing. The interiors are equally beautiful with stained glass windows lighting up a nave which is pillared and arched, and a chancel that is fan vaulted and panelled.

The construction of this structure, initially referred plainly as General Kennet’s Church, in honour of the man who donated the piece of land on which it stands, appears to have been by no means smooth. Heavy rains are reported to have washed away the tower and part of the eastern wall in 1852, and though repairs were effected the same year and a new tower was constructed on the western end, it took another couple of years for it edifice to be finally consecrated.

The building which was sanctified on 18 March 1854 was a small structure with a seating capacity of just 200 individuals, and although it had a fine tower it lacked a regular chancel. It was only in 1879 that measures were taken to correct this deficiency, but the chancel had to be altered in 1894 to accommodate the newly acquired pipe organ.

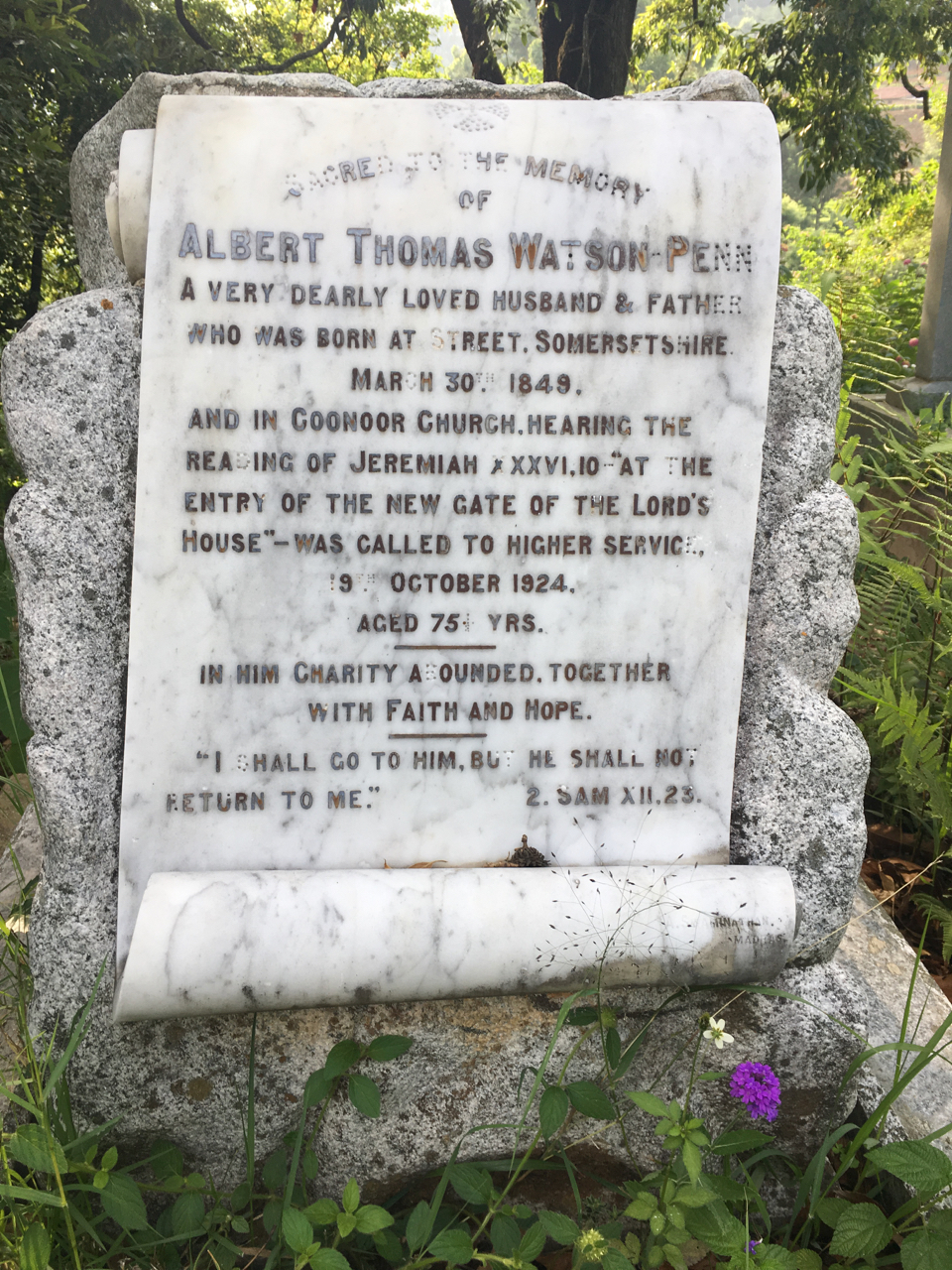

The churchyard of All Saints which was officially closed in 1909, boasts many a famous grave. The most prominent of these are those of Major General Brackley Kennet of the Bombay Army who donated the land and Rev Dr Frederick Gel, Bishop of Madras and the earliest among the Anglican Clergy to moot Indians for bishoprics. Others are those belonging to the Stanes family ; that of the earliest of hoteliers Charles Gray and Davison of Gray’s Hotel and Glenview. Lt. General Richard Hamilton the founder of the Coonoor Club is as well buried here.

The Tiger’s Hill Cemetery attached to the church was opened in 1905, and is a quiet spot of fairly level ground shaded over with spreading umbrageous white oaks. A. T. W. Penn pioneering photographer of the Nilgiris, Sir Frederick Adams Nicholson founder of the cooperative movement, Charles Eagen of Hill Grove Hotel, Henry Arthur Popley translator of the Thirukural, and Charles McFarlane Inglis Curator of Darjeeling Museum, are a few well known individuals interred here.

Unfortunately this cemetery owing to its remoteness has been of late subject to vandalism, and presents a sorry spectacle of desecrated tombs, faded letterings, missing inlays, broken statuettes, and so forth.

Her Railway

Scroll down to listen to the next section

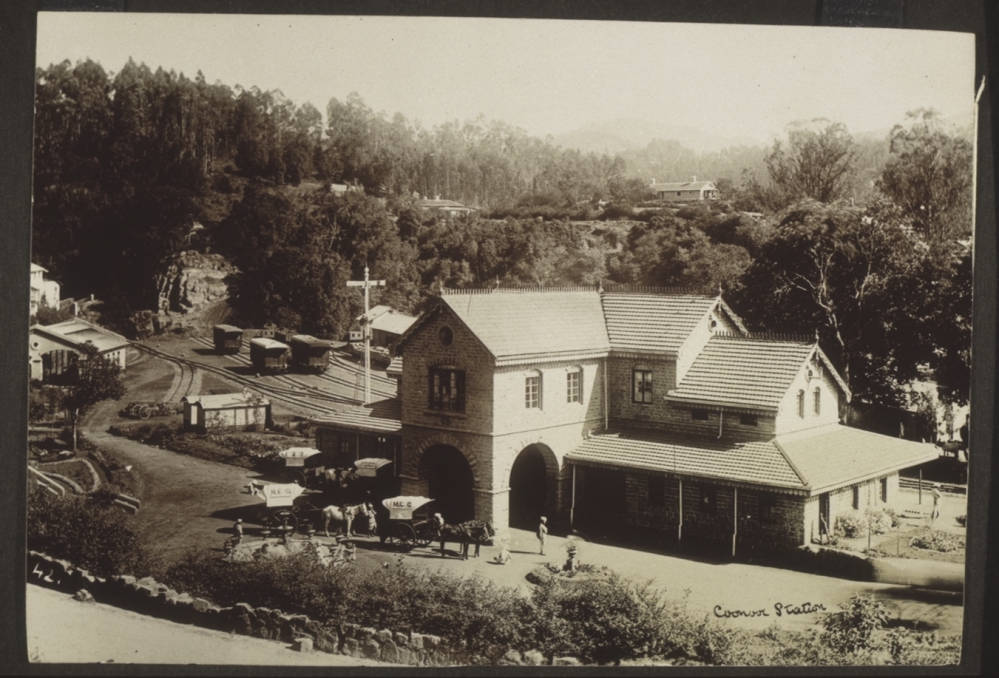

The first rolling stock of the Nilgiri Railway Company chugged up these hills as on June 1899, and the fifteenth of this month is observed as the Nilgiri Mountain Railway Day, to mark this event.

This Mountain Railway of India which was listed as a World Heritage Site by the UNESCO on 15 July 2005 traces it roots way back to 1854, when plans for something akin to a railway were afoot even before the present road was ever laid.

Schemes for a railway up the Coonoor Ghat began even before the present road was ever laid, but serious consideration about the matter began only in 1874. The Swiss Engineer and inventor of the Rigi system of mountain railways, Monsieur Niklaus Riggenbach, offered to construct this line in 1876, but his offer was turned down due to financial considerations.

An alternate project was proposed in 1877 by the Duke of Buckingham, which provided for a regular railway from Mettupalayam to a point about 3 kilometres (all distances given in kilometres rather than miles for easier comprehension) north of Kallar, and thence an inclined ropeway to Lady Canning’s Seat. This again fell through for not only was the proposed cost was almost as much as Rigenbach’s, but also for the reason that pulling up passengers up such a steep incline was considered to be a hazardous undertaking.

It was Major Morant of the Royal Engineers who took personal interest in this issue and invited Monsieur Riggenbach to come over to the Nilgiris in 1880, and work up an estimate for a rack railway from Mettupalayam to Coonoor. The upshot was a ‘Railway Committee’ being formed with Sir Robert Staines as the Chairman, with Major Morant, Riggenbach, and thirteen others as members. The committee met at the library at Ootacamund on 16 March 1880, and a Limited Joint Stock Company called the Coonoor Railway Company (Limited) was proposed.

Owing to an unsatisfactory public response, necessary funding wasn’t forthcoming, and a new company called the Nilgiri Railway Co., was formed in 1885, and though it dropped the proposal for a Rigi Line in favour of an adhesion line, the rack principle eventually found favour again. It was not until August 1891 that work commenced, the first sod being cut by Lord Wenlock the then Governor of Madras.

This company was unable to complete the line and went into liquidation in April 1894 and a new one was formed in 1896 to purchase and finish the line, which finally opened in June 1899, and was worked by the Madras Railway under an agreement. The government eventually purchased the line in 1903, but it was still worked by the Madras Railway on certain terms, and it was never considered as a profitable venture. It was for this reason that the line was extended to Ooty, as it was soon recognised that without this extension, there was small probability of the project proving to be a financial success.

A decision to continue the rest of the track as an adhesion line along an easy but circuitous gradient was finally made, and work began with the line being declared as open to traffic on September 1908.

Early Picnic Spots

Scroll down to listen to the next section

In the 1840s, Coonoor was just a stopover for many a weary pilgrim, trudging on in his annual hegira to Ootacamund, and fleeing from the sweltering heat of the hot and dusty plain below.

Coonoor then was a flyspeck on the map, when compared to her elder sister, Ootacamund. All the accommodation she had to offer was a well kept hotel called ‘Davison’s,’ and an ill-kept traveller’s bungalow which once stood over the present-day court premises, and which one early haji depreciatingly describes as the ‘thing’ perched on the top of a hill, with broken windows, fireless rooms, and tasteless meals.

She had just three excursions to offer, a visit to Castle hill aka Coonoor Betta aka Tenerife ; another to a Toda village where the present day Wellington Gymkhana Club now stands, and yet another to the Hulical Droog.

It is from Lt. Richard F. Burton that we know about these early places of interest, who in his customary ungracious manner, dismisses the first as a very second rate prospect, and the second in terms which would rather not be mentioned here. But when it came to the third, the Hulical Droog to be precise, Burton is strangely eloquent to the point of being lyrical.

The route to this spot now runs chiefly through many a tea estate, but in Burton’s time, looks to have been entirely clad with vegetation which he calls as ‘the forest primeval.’

Part of this early route roughly corresponds with the one which is marked in the older maps as the ‘Old Katerri Road.’ According to Burton it descended steeply down a rugged hill from behind the present day court-complex, crossing what he calls a couple of detestable watercourses, before reaching the whereabouts of what is now the first bifurcation one comes across whilst travelling from the Kateri junction towards Kundah.

From here the path appears to have been precipitous but a thoroughly enjoyable one, for according to Burton, it plunged through a mass of noble trees rising in all their sylvan glory, and ran through a forest floor carpeted with crisp fallen leaves. Below the dizzy steeps of the foot-track and between the tree trunks that lined it, a grand view of light mist-clouds and white vapours sailing on the zephyrs far below was to be had, while the wind kept murmuring above the leafy dome all the time. After such an arduous but ecstatic hour, the Droog rather suddenly, sprung into view.

The fort looks to have been in a ruined state even at that time, for only a part of the parapet wall was all that remained.

But the view seems to have been magnificent, and to a certain extent still is, for from the ruined parapets, the rock upon which it stands, falls with an almost perpendicular drop of four thousand feet, offering a spectacle which Burton states as one which even a jaded lionizer would admire.

From this eyrie, one could descry the houses of Coimbatore, the windings of the River Bhavani, the roads stretching ribbon-like over the glaring yellow surface of the lowlands, with the bluish mist clad hills of distant Malabar appearing dimly over the horizon. Behind the mighty chasm on the far side, could be seen the white bungalows of Coonoor glittering through the green trees, disappearing now and again behind veils of fleecy vapour which floated along the sunny mountain tops.

Though hypercritically disposed, Burton finds no fault with this view, the latter having had beauty, variety, and sublimity to recommend it.

In the 1850s, Coonoor acquired yet another place of interest with a grand view. It was named by the then Collector of Coimbatore, Mr E B Thomas, after a certain Captain Lamb, who had gone into the trouble and expense of cutting a path to it. Lamb’s rock as it is still called, is a sheer precipice of jagged rock which drops down several hundred feet to bury itself in the luxuriant jungle below.

The best among the later day additions is the park laid out in 1874, by the Honourable J. D. Sim, C. S. I, Member of Council in 1870-75.

Although overshadowed by the Government Botanical Gardens, Sim’s Park with its well-kept lawns and artistically laid out ornamental beds, lacks no wealth of flowering plant or shrub in great variety and colour.

The scenery alongside this park was once described as exquisite, for nowhere on the hills was there to be seen such a profuse growth of the graceful tree-fern, and many other of the smaller varieties of beautiful ferns was to be found. One account states that there were also fine stretches of shola, rich in flaming rhododendron, and with wild flowering plants and trees, all growing as nature herself had planted and preserved them in their primeval beauty.

Municipal

Drainage

Scroll down to listen to the next section

Before being constituted as a municipality in 19 October 1866, Coonoor Town appears to have depended on the steepness of its hillsides and on heavy rains to scour the debris accumulated pretty thoroughly, before emptying it along with the runoff into the Coonoor River. But in those far of days, this didn’t matter much for the population was just around 3,058 souls dwelling in 536 houses.

But a little later, serious notice about this state of affairs was taken up by the government based on reports, and it started to persistently press the council for a proper drainage system, but, the council on its part, appears to have been equally persistent in its plea, ‘impecuniosity!’

It wasn’t until 1885, after much discussion and dillydallying, that the municipal overseer finally prepared the first plans and estimates. The initial plan divided the town into Bazaar Hill and Mission Hill, which were treated separately, and provided for open drains which emptied into covered sewers, one for each hill, each leading to a common iron pipe which would discharge the contents into the river just below the present bridge.

It was the Sanitary Engineer who realised the perils of such open drains and came up with an alternate but slightly expensive proposal, which provided for semi-oval cement or stoneware street drains, with the intercepting and outlet sewers made of stoneware pipes, with the outfall through a 12” iron pipe, bolted to a rock in bed of the river and at a spot where water flowed perpetually.

The council started the work in 1891, after the Government made over to it a free gift Rs. 30,000, and another Rs. 12,500 as a loan to be repaid in 20 years. The sewerage system was in place the next year with the pipes being purchased from Burn & Co. of Calcutta.

Unfortunately due to the topography of Coonoor and the paucity of funds, no provision for sewage treatment was made at the outfall.

Whither has vanished the stoneware pipes and the closed drains, still remains and will remain one of Coonoor’s unsolved present day mysteries, and the whole river which flows past the market is presently one large open sewer, often choked with filth and garbage of all description. Such is the sorry state of affairs that the small picturesque fall below, named after Colonel G. V. Law, and which was once a much frequented picnic spot, is no longer one, on account of the unbearable stench, particularly when the river is slow.

Sewage treatment as far as Coonoor is concerned appears to be an uphill task which needs much planning. Its steep slopes which once proved to be a boon, are now a bane, for they make the installation of a single treatment plant almost impractical, and also so are the haphazard constructions and the overcrowding, the population having exploded to around a little above 50,000 individuals.

Water Supply

The first effort to supply a part of Coonoor with drinking water other than that obtained from shallow wells and such like, was a private albeit unauthorised one. Records show that one Mr Lascelles, cut an open channel from a spring at Ottupatarai marked in the older maps as the Milk Village, to supply ‘Woodcote’ which he had built in 1847.

In 1871, the Municipal Council took it upon themselves to improve and realign this aqueduct and extend its benefits beyond Woodcote to the three houses called Balaclava, Alma, and Inkerman, all named after the three battles of the Crimean War and which were collectively known as the ‘Crimean Properties’ of General Cleveland. The houses on the other side of the valley were again supplied by open channels from various sources, which down their course, were polluted in every sort of way.

Such was the situation, till the Surgeon-General in 1888, reported in rather forcible language the sorry state of affairs, and a plan to provide safe drinking water was finally put forth by the Sanitary Inspector in 1891.

This plan called for leading an existing channel which ran through Yedapalli to the region around Sim’s Park where settling tanks and a service reservoir would be set up, and distributing it thence throughout the town by pipes. But again the question of pollution where a long and open channel was concerned arose, and after further planning it was decided have a piped supply tapped from the Wellington Stream by laying a low dam across it. This alone proved insufficient and it was decided to additionally tap part of the branch of the stream which supplied the Wellington Cantonment, and this was done after much haggling with the military authorities, which ended only after the intervention of the Government of India.

Slight alterations were made in 1903, and it was finally decided that the service reservoir with its two day distribution capacity was to be placed on Gray’s Hill, along with an extension of its distribution lines, and the supply from the Milk Village which provided water for the western half of the town, was as well to be piped. The headworks were completed in 1905, and a year later the distribution system was finished and the project reached fruition.

With the construction of the Ralliah Dam in 1941, an uninterrupted safe drinking water supply was further ensured.

Today Coonoor faces perennial water shortages, and the usual scapegoat is ‘Monsoon Failure.’ Introspection will reveal that it is wastage through utilisation for other purposes and leakage ; silting of catchment areas due to anthropogenic activities ; diversion ; so forth, are the real culprits.